The #ENDSARS #ReformPoliceNG campaign began in 2016 (but garnered more attention online in December 2017) as a protest to the incessant brutality of the Special Anti-Robbery Squad, SARS against Nigerian citizens. The SARS is a specialized arm of the Nigeria Police Force, established to combat armed robbery and other violent crimes. (1)

During the #ENDSARS campaign, Akanka was contacted by Ikechukwu Uzoma, an International Law and Human Rights Fellow at the United Nations, to collaborate on a survey he had put out in a bid to collate some data on the campaign. Dr Arowolo Ayoola of Data-Lead Africa also contributed to the survey’s design.

While analysing the survey’s data, Akanka garnered some insight into the supposed activities of the SARS. Unintended, the survey results also provided some insight on online surveys that could assist students or researchers conducting future surveys.

We’ve included a more holistic analysis to the graphs in the Tableau Visualisation, grouped by demographics of responders, the time, and the nature of harassment by the SARS.

On Demographics of Respondents

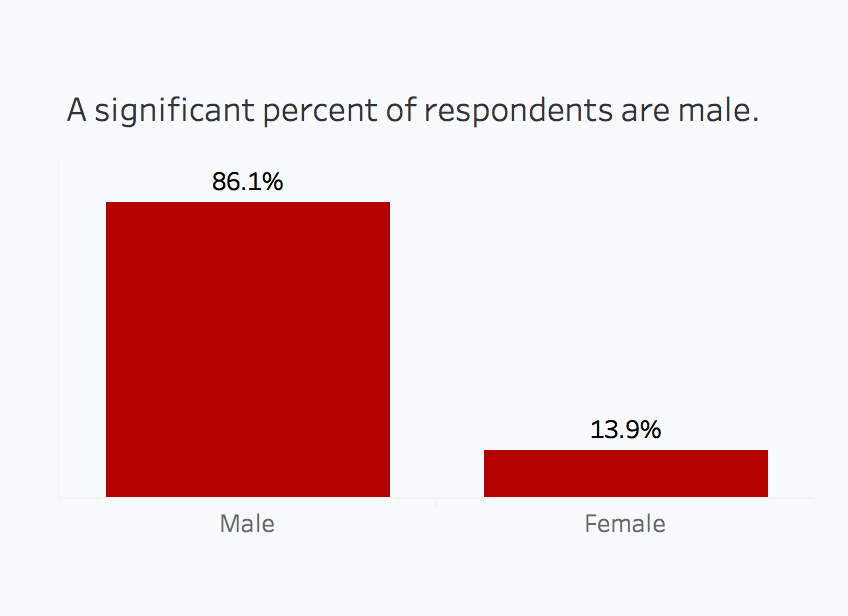

Gender

The likelihood that the SARS would arrest men is significantly higher than the likelihood that they would arrest women. This could be for two reasons:

- It is easier to accuse men of robberies and other violent crimes.

- Nigerian men are more likely to have higher disposable incomes than women and can be extorted for a higher payout. This is simply conjecture and might not necessarily be the reason for the increased likelihood of male harassment. However, these are the most likely explanations.

Interestingly, when women are harassed they are accused of prostitution, which clearly does not fall under the purview of a special anti-robbery squad ( and clearly should not be classified as a crime).

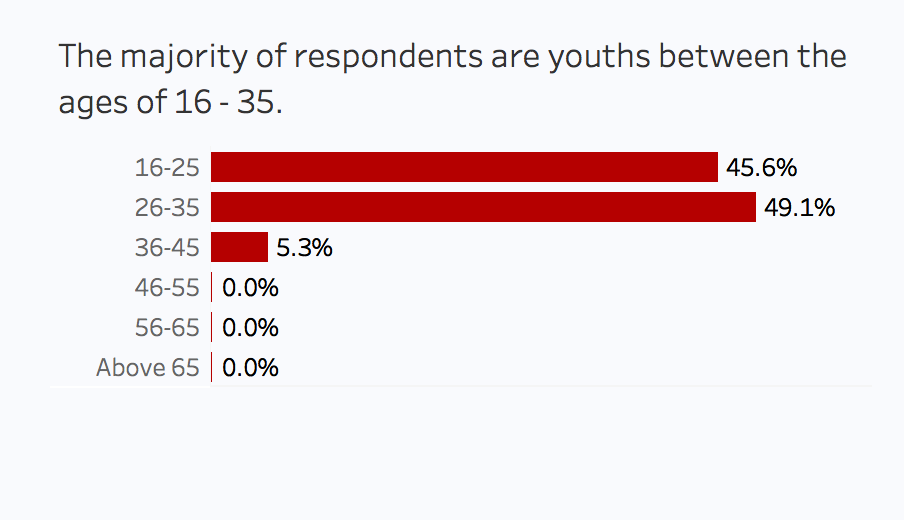

Age

The SARS’s proclivity for stopping young people explains why the majority of respondents are youths between the ages of 16–35. It could also be the case that Nigerian Twitter largely consists of individuals between the ages of 16–35, which makes them most likely to be the majority respondents. This is known as selection bias, where a characteristic of the survey strongly influences who fills the survey. A larger test that included respondents from facebook or offline sources might yield a different age spread.

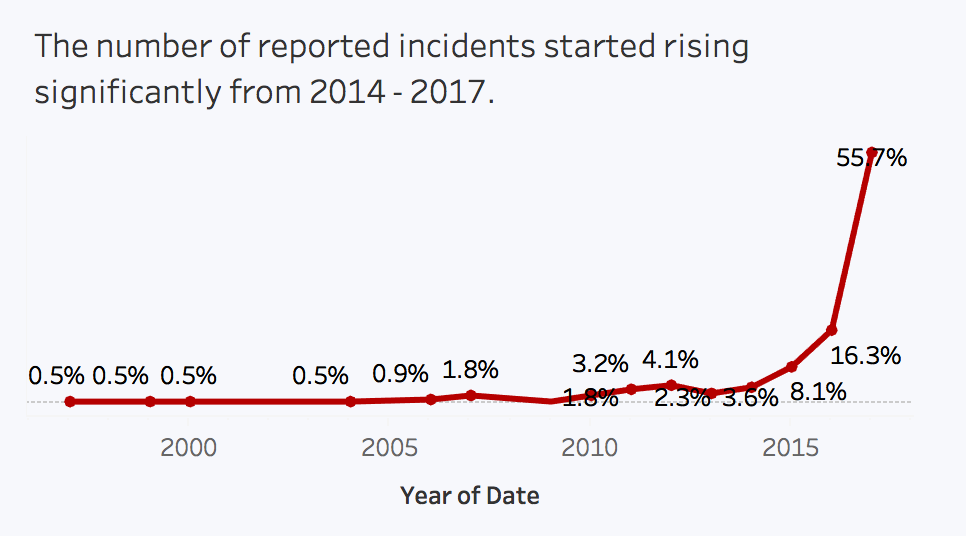

On Times of Harassment

The significant uptick in the number of reported incidents with the SARS could be an indication that the predatory activities of the SARS increased over the years. It could also be that people who had recent experiences with the SARS have a more vivid recollection of the experience, are more emotionally attached, and are therefore more likely to fill the survey. This is known as recency bias. Reframing the call for respondents by including a time period “2000-Present” might incentivise those with past experiences to fill the survey.

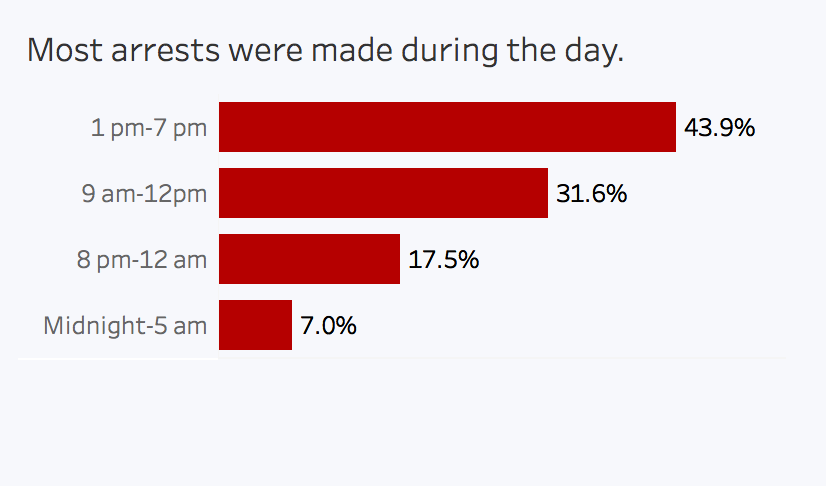

The data reveals that most arrests are made during the day, which is puzzling considering that the SARS is an anti-robbery squad. However, this does not mean the SARS isn’t active at night (when they most likely need to be), it just means they spend a significant part of the day disrupting the lives of innocent Nigerian citizens.

On Accusations & Nature of Harassment

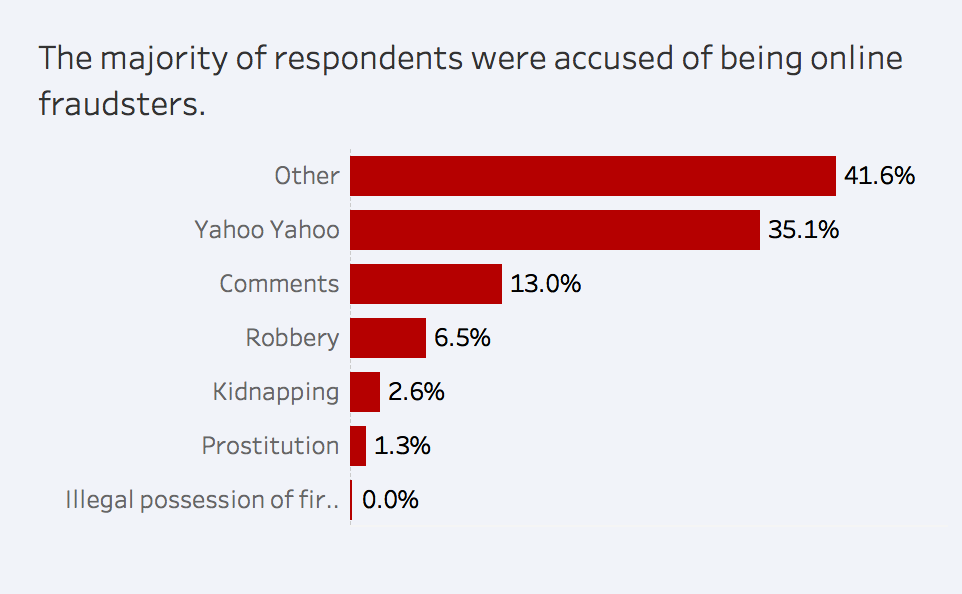

The majority of respondents were accused of being online fraudsters. Interestingly, only 6.5% of respondents were accused of robbery by the anti-robbery squad, which indicates a disconnect between the SARS’ original duty and its actual activities.

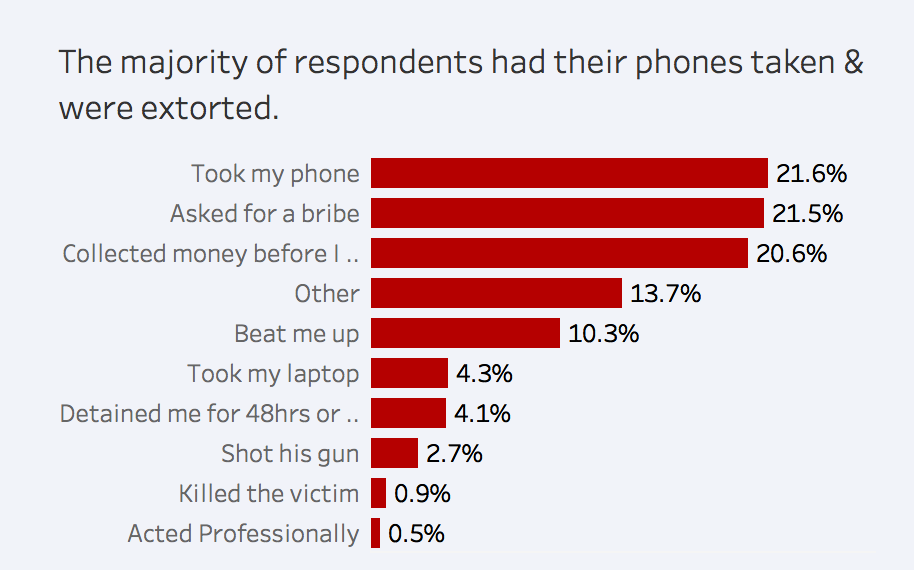

The majority of responders accuse the SARS of taking their phones, which correlates with the high number of accusation of online fraud. If the police has repeatedly stated that the phones of citizens cannot be searched by the police, why then does the SARS continue to do so?

However, a survey design implication could be that people who have phones and get them seized are most likely to be the highest respondents on Twitter — another case of selection bias.

In spite of the considerable number of stories on social media involving the extrajudicial murder of victims, accusations of murder come in as the least frequent action taken by the SARS. This does not necessarily indicate that the SARS do not engage in extrajudicial killings. Instead, it could simply confirm that “dead men tell no tales”. Third-party reports about victims who go missing corroborate responses from respondents that victims are randomly arrested and switched out for criminals who can afford to bribe the SARS officials. This was confirmed by one survey respondent who stated that the SARS threatened to kill him and use him as a replacement for a prisoner whose parents were willing to pay handsomely.

On the absence of a visualisation showing places of the SARS encounters

A number of individuals on Twitter asked for a visualisation of the states these reports originated from. Unfortunately, due to the design of the survey question on location of incident, cleaning, processing, and analysing the data would have required a manual and highly cumbersome effort. A dropdown option with a list of states should have been used in the form, rather than an input form. The use of an input form meant there was no standard to the answer of location. Answers ranged from the desired response – the state where the incident occured- to the undesired and oddly specific answers like “Total Filling Station near Illupeju”. One would have to go through each entry manually to parse out the state the incident took place in. Data gathering that involves a qualitative response should allow for freedom of respondents answers. However, data that needs to go through analysis to extract statistics can only be efficiently acquired by applying a constraint to the freedom of respondents’ answers.

The survey received 248 responses over a period of 2 weeks. Statistically, the more accurate responses the survey receives the better the quality of data. Collating more responses from individuals offline should offset the biases that are inherent in the current survey. As beneficial as this is statistically, the real life implication is far less pleasant — more responses indicates the rising harassment of Nigerian citizens by the SARS. As it is, one case of the SARS harassment is far too many.

Main Takeaways

- Take note of the data points that are not included or appear to be absent. For example, the lack of older people in the results. What may seem like non-events are important for the reasons they are absent and can tell you more about the nature of the survey.

- Where you conduct surveys can be as important as the questions in the survey. Note that an offline or online survey could isolate an inaccessible segment of the population. e.g. those without internet.

- More time spent designing survey questions reduces the effort needed to clean, process, analyse and visualise the data.

- Clearly, the veracity of all respondents cannot obviously be determined considering the anonymous nature of the survey. By asking specific questions about location and experience, we’ve tried to reduce the likelihood of fabricated reports. However, this is no guarantee. A consequence of such non-documented harassment is that paper trails/documentations of arrest(which would be a more accurate method of verification) are deliberately absent i.e. not provided by the police. Invisible data is invisible for a reason.

- A clear misalignment exists between the mandated responsibilities of the SARS and their actions on the Nigerian citizens — reforming the SARS should be a priority of the Nigerian Police Force.

As always, thanks to Mohini Ufeli for reviewing and editing.